Table of Contents

This chapter is a short, casual introduction to Subversion. If you're new to version control, this chapter is definitely for you. We begin with a discussion of general version control concepts, work our way into the specific ideas behind Subversion, and show some simple examples of Subversion in use.

Even though the examples in this chapter show people sharing collections of program source code, keep in mind that Subversion can manage any sort of file collection—it's not limited to helping computer programmers.

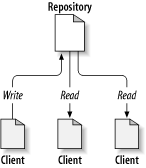

Subversion is a centralized system for sharing information. At its core is a repository, which is a central store of data. The repository stores information in the form of a filesystem tree—a typical hierarchy of files and directories. Any number of clients connect to the repository, and then read or write to these files. By writing data, a client makes the information available to others; by reading data, the client receives information from others. Figure 2.1, “A typical client/server system” illustrates this.

So why is this interesting? So far, this sounds like the definition of a typical file server. And indeed, the repository is a kind of file server, but it's not your usual breed. What makes the Subversion repository special is that it remembers every change ever written to it: every change to every file, and even changes to the directory tree itself, such as the addition, deletion, and rearrangement of files and directories.

When a client reads data from the repository, it normally sees only the latest version of the filesystem tree. But the client also has the ability to view previous states of the filesystem. For example, a client can ask historical questions like, “What did this directory contain last Wednesday?” or “Who was the last person to change this file, and what changes did they make?” These are the sorts of questions that are at the heart of any version control system: systems that are designed to record and track changes to data over time.